Searching for the Sounds of the Ancient Maya

- © Efraín Figueroa Lemus

- May 1, 2021

- 6 min read

Replica of thistle-shaped Maya drum

Sitting in a row inside a narrow palace chamber, somewhere in what is today the Petén lowlands of Guatemala, a Maya lord, perhaps a visitor from a distant citadel, is entertained with samples of different foods carried by his host's servants. With a gesture of the hand, the host seems to invite his guest to taste all the culinary delicacies before him.

To add to the celebration, two musicians with exuberant feathered headdresses and tattooed bodies play their instruments on the far left of the scene. The first plays animatedly a pair of rattles, with an expression that also suggests singing. To his side, another musician embraces a horizontal drum, marking with his open hand the beat of their performance. Given the solemnity with which the banquet is being offered, those musicians must be the best in many leagues around.

Banquet and music scene, classic Maya vase (Justin Kerr - K1563).

Little is known about the music enlivening the private banquets of the Maya lords. Like other expressions of their culture, the music of the Maya underwent radical changes after the Spanish invasion and with the passage of the centuries.

But the scene left in this polychrome vessel, one of several that have survived with similar images, provides a conduit through time to eavesdrop on the Maya palatial sounds. From such scenes one observes that percussion instruments were predominant in the music of the Classic Maya: we find large and small cylindrical drums, turtle shells, clay rattles and gourd rascadores. These instruments formed an orchestra by themselves, or could accompany the sounds of flutes, ocarinas, trumpets and the human voice.

Of their percussion instruments, the drum shown in the previous vase scene attracts particular attention due to its unique shape and its effect on the resulting sound. By reproducing its sound, one can then recreate the sonorous environment of that meeting of 1,500 years ago, so vividly represented in the vase.

The drum in question was played by holding it horizontally under one arm and striking it with the other open hand. It was small and portable enough to be played standing up and even walking in a procession. In fact, musicians are often shown playing it while also sounding other instruments, such as a rattle or flute.

The characteristics of this drum are its broad neck where the hide (likely deer skin) is stretched, connected to an oblate spheroid, and followed by a narrow conical section ending in a flare. If drums from other parts of the world are described as cup-shaped, this Maya drum has the shape of a thistle cup. Not knowing its original name, we shall call it a thistle-shaped drum. As we show below, its shape is fundamental in the generation of its peculiar sound, and gives us an idea of its use within the Maya percussion orchestra.

Thanks to the fact that the thistle-shaped drum was made of clay, several examples survive to this day. At the Museum of Anthropology and Ethnology in Guatemala City one can admire a drum in an admirable state of preservation, formed very delicately in orange clay, with details painted in red and black resembling the rosettes of the jaguar skin. It is one of an almost identical pair of drums excavated from the site of Uaxactún, in El Petén. Another example, with different ornamentation, was found in Nebaj, in the central department of Quiché, Guatemala, also on display at the same museum. In addition, drums of this type are reported from Belize and, more recently, from the Waka-Perú site, also in El Petén.

Thistle-shaped Maya drums from (a) Uaxactún (b) Nebaj (MUNAE, Guatemala)

Superficially similar, other drums have appeared in Africa (see the djembe) and countries in the Middle East. In the latter case, the instruments are also made of ceramic, and played similarly to the Mayan style: horizontal, under one arm. We find, for example, the doumbek or darbuka in the Middle East, with its conical resonator and flared neck, and the tonbak of the ancient Persians. These drums are characterized by their cup shape, with the animal hide stretched on the wide opening, and a long, narrow neck. The Maya also used a drum of the cup type. Nevertheless, the Maya thistle-shaped drum is unique, not only in its construction, but in its acoustic properties, as we will show next.

Cup-shaped drums of the world: a) Middle Eastern doumbek or darbuka b) Persian tonbak

(c) Burmese klong yao (d) Maya (Atitlán, Guatemala).

The ingenuity of the Maya instrument maker

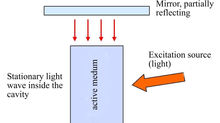

Unlike the instruments of the Middle East, the Maya thistle-shaped drum has the complexity of being segmented into three compartments, each of which is in itself a resonator: the upper cone that supports the stretched animal hide, the intermediate globular body, and the long tapered outlet tube, ending in a flare. That is, the drum consists of three resonators coupled together. The result is an instrument whose fundamental frequency is very low, typically below 50 Hz, depending on its dimensions.

We can then appreciate its special characteristic: without having to be too tall or bulky (like the most common pax or vertical drum from the same culture), the thistle-shaped drum is capable of producing a very grave tone, akin to a rumble, in a light and portable instrument.

In order to design it and achieve the desired effect, the Maya experimentalist must have intuited the contribution of each part of the drum, since, as we recently verified during the making of a clay replica by an experienced artisan, considerable skill and care are needed to build the entire piece. It is possible that the architect of the drum was simultaneously a skilled artisan, or that he collaborated with one who was such. The fact is that this novel drum was well received by the Maya musicians of the time, as we find it in distant areas of Guatemala and Belize, and quite possibly, in other areas of the Maya world.

Acoustics of the Maya thistle-shaped drum.

While the African globular drums and those of the Middle East can be modeled as a system of a single spring and mass (equivalent to the air compressing and expanding within the resonator, driving the air in the neck into an oscillation), the thistle-shaped drum must be modeled as three coupled oscillators. This is because its body is made up of three sections connected to each other (numbered 1-3 in the diagram below). Each of the three sections can be a drum in itself. Of the three solutions (frequencies) that result when solving the equations of motion for the three coupled oscillators, the lowest frequency corresponds to a mode where all oscillators are in phase. Getting such a low tone with a simpler structure, like the djembe, can only be achieved at the expense of a very large volume or exaggerated length of the neck. We can thus appreciate the ingenuity of the Maya experimentalist in achieving a similar effect from a compact, portable instrument. To make the sound radiation more efficient, the designer also formed the exit of the third section like a trumpet or flare.

Modeling the thistle-shaped Maya drum as three coupled

resonators: 1-conical, 2-globular, 3-conical.

We can guess that the Maya thistle-shaped drum was the "bass" in the percussion orchestra. Although multiple effects can be achieved by tapping the hide near the drum's edge (exciting higher modes in the circular membrane), striking it with the open hand at the center excites the fundamental mode or the resonator, producing a sort of deep rumble. We can imagine that, played inside a narrow room, the effect would have been very dramatic, accompanied by clay rattles, gourd raspadores, and flutes or whistles. The drum was an instrument to mark the beats of an interpretation and induce movement in the dancers, giving a dramatic atmosphere to each performance. Its sound could emulate the deep rumble of an earthquake, of thunder, or the pulsations of the heart.

How does each part of these globular drums contribute to their sound?

A simple resonator, such as a clay jug, can be modeled physically by the theory of Helmholtz resonators (in honor of Hermann Ludwig von Helmholtz, a physicist who studied the perception of sound using globular resonators in the mid-nineteenth century). It consists essentially of a single wide compartment, either conical or globular, inside which air is compressed or expanded in the manner of a spring, causing the air in the neck to oscillate back and forth, and in turn, radiating a sound wave to the outside.

An example of such a simple resonator is the African udu, one of many universal instruments based on round clay pots. The lowest frequency of such resonator is proportional to the square root of the area of the neck (A), and inversely proportional to the square root of the product of the volume of the vessel (V) and the length of the neck (L). That is, the tone produced by said drum becomes lower as the volume increases, or as the neck lengthens. Likewise, the sound is deeper as the neck diameter gets smaller. In drums such as the darbuka and the djembe, the air chamber is a truncated cone connected to a long neck, often with a flared end.

To listen to the sound of replicas of the thistle-shaped Maya drum, joined by other instruments of the ancient Maya, click the video below. Since most computer speakers do not reproduce such low frequencies, it's recommended to use headphones.

* Efrain Figueroa Lemus, PhD physics, is the author of "La marimba mesomericana: una historia ilustrada", Editorial Piedra Santa, Guatemala, 2016.

![endif]--![endif]--![endif]--![endif]--

Comments